7. THE DESIRE FOR MEANING

On absent absolutes, man-made mysteries, and Solenoid by Mircea Cǎrtǎrescu

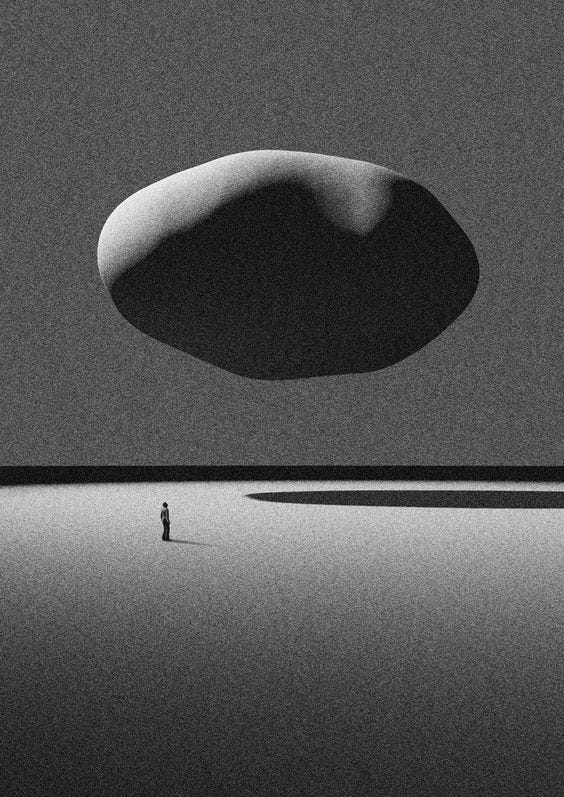

We are obsessed with building labyrinths, where before there was open plain and sky. We cannot abide that openness: it is terror to us.1

While reading Solenoid by Mircea Cǎrtǎrescu, translated fantastically by Sean Cotter, I thought often of the human necessity (and perhaps folly) to mine for meaning in meaninglessness and to construct meaning when we fail to find it. Solenoid is a perfect example of literature that enacts humanity’s tendency to complicate the simple, to read order in chaos, and to fabricate mystery where there is only shallow fact. Though we might express the desire to find answers to our mysteries, it is in fact the truth’s continued obfuscation that we long for. Just as we cannot comprehend nor accept a true end, neither can we stand the absolute of an answer, the definitiveness of fundamental truth. Were it presented to us, we would not believe it. What comes after the absolute answer? we might ask. What caused it? What is the reason for it? What is the answer to the question posed by the answer? Despite the finitude of our lives, cosmic finitude is incomprehensible. No end is or will ever be enough.

And thus it is just as well that the universe cannot provide such absolutes—there is, after all, no such thing as a final answer, a total truth. If meaning exists it does so only locally, at certain scales, in certain times and spaces. In realising this, in perhaps sensing the ultimate meaninglessness of the cosmos, the emptiness of reality—and in fearing that emptiness—we cloak it in layers and layers of false meaning. We convert the straight road into a maze, not out of a conscious desire to complicate but out of an inability to accept that reality may in fact be inordinately simple, lacking in depth and substance. The unnamed narrator of Solenoid seeks, above all, an answer:

I was enveloped in a fear that I had never felt before, even in my most terrifying dreams; not of death, not of suffering, not of terrible diseases, not of the sun going dark, but fear at the thought that I will never understand, that my life was not long enough and my mind not good enough to understand. That I had been given many signs and I didn’t know how to read them. That like everyone else I will rot in vain, in my sins and stupidity and ignorance, while the dense, intricate, overwhelming riddle of the world will continue on, clear as through it were in your hand, as natural as breathing, as simple as love, and it will flow into the void, pristine and unsolved.2

His life is consumed by this quest, which he sees as the most vital, most noble of all human endeavours, and Solenoid is its record, the meticulous accumulation of facts which, the narrator believes, will ultimately—if joined together exactly right—reveal the truth of human existence and suffering.

This search for understanding is a theme not only in Solenoid but in human thought, and it is perhaps an error. That there are things beyond human comprehension is undeniable, but that meaningful mysteries underpin the world, the universe, and all of reality, strikes me as some kind of desperate wishful thinking—the allure of which I, myself, am not capable of resisting. Recently I stuck a list above my bed entitled “Books that may contain answers”. I did not specify on paper what kind of answers I was looking for, nor have I done so in my mind: the vagueness of my search is vital for its continuation. Like all good mysteries it feeds on its own emptiness. I don’t know what I’m seeking which gives what I seek the ability to change, to grow, in effect to survive, year after year, even as I change and my interests along with me. What I count as clues are equally ambiguous: snippets from premodern poetry and prose, factoids on higher dimensions, books that speak of spheres or labyrinths, mathematical and natural symmetries, philosophical or logical paradoxes. My collection of evidence is as varied as it is nonsensical and yet I hunt through it desperately for some common denominator, some pattern…

Even in the awareness of my error, I continue to make it. I cannot help myself. To abandon my search would be to abandon my meaning, my life. I speak openly of the meaninglessness of existence but cannot quite accept it. The knowledge sits in my mind like a hard, shiny ball in the midst of a murky liquidity; it is discrete, impenetrable, and incapable of fusing with the rest of my psychology; my thoughts roll off it like water. In the end I prefer to live my days in the warm illusion of meaning. And books such as Solenoid only feed that illusion—even if such a novel pushes us right to the limits of meaning, fills and encompasses so totally the realm of meaning that should one’s mind take a single step beyond it we would drop smoothly into the abyss.

Early on, the narrator of Solenoid admits to us that his life has been characterised by a series of what he calls “anomalies”—bizarre events that stand out as incongruous with the banality of everyday reality. Slowly throughout the novel’s 600+ pages, the narrator recounts these anomalies for us, which only grow more and more surreal as the book (and his life) unfolds. These anomalies are his clues, his evidence pointing to a deeper truth, an answer to those grand metaphysical questions: Why am I here? What is my purpose? Why does the world exist? But they also add to the unreality of his existence.

The world of Solenoid—which our narrator makes clear is in fact only Bucharest, the world beyond so unreachable that it might as well not exist—is characterised by the surreal. It is a surrealism superimposed upon the real, so that, ironically, it is the real that becomes strange, nestled amongst the ordinary beats of wicked fantasia. Our narrator says,

I live in such a strange world: it might not be reality, it might be a stage set built for me, one that will disappear as soon as I stop perceiving it. How often have I thought I could whip around and catch the stuttering stagehands knocking the backdrops together, see the single wall of the propped-up buildings fall over, or catch the moment when all perceptions dissolve into the void of death!3

But one also gets the sense that the fantastic elements of the novel are not really real—that they are, instead, an exaggeration of the narrator’s distorted perception and experience of reality. Solenoid never tells us what is real and what is not, what is a projection of the narrator’s internal life and what is exterior, and indeed, it isn’t interested in clarification. The result is a persistent ambiguity, a dream-like haze which hangs over the places and people and events of the narrative. We enter a normal scene and out of nowhere, in the course of a sentence, through the introduction of a single uncanny element, the entire world slides over into the fantastic. We are haunted by the feeling of being in two places at once, of being caught midway between our own mundane reality and a horrific fantasy, fuelled by the distorted impressions of an outcast.

This real-not-real effect is the product of Cǎrtǎrescu’s literalisation of metaphor, which he takes to extraordinary extremes. The narrator’s feeling of estrangement from his house, for instance, is not conveyed through a metaphor of the house as strange; rather, Cǎrtǎrescu writes:

I got lost in my own home. I never really knew how many rooms, hallways, staircases, and corridors it had, and often, on my way to the bedroom, I ended up in dens of bathrooms that were not only completely foreign to me, as though one of the walls of my house had disappeared and another house had been grafted onto it, but also from another time, another space, another memory. . . . I only found my bedroom the next morning, exhausted by dozens of kilometres of corridors, by the mechanical operation of thousands of light switches, by the desperate repetition of opening hundreds of doors, hoping every time to see, finally, my rumpled bed in the center of this mandala of corridors. . . .4

Cǎrtǎrescu could have written that the narrator’s house “felt infinite” and been done with it, but instead he describes for us a literally infinite house, one whose territory expands and contracts, grows in strangeness or familiarity, according to the narrator’s mental state. Although we as readers sense that the narrator is exaggerating—surely, we think to ourselves, he did not literally walk through the house all night—Cǎrtǎrescu’s literal language renders the problem indeterminable, answerless. Is this a fantastic world perceived as ordinary or an ordinary world conveyed as fantastic? There is no possibility of settling on one answer or another. We proceed through a text that is incessantly shifting beneath our feet, as though through a house whose foundations are forever being rebuilt, even as we continue to live within it.

In such a world the anomalies of Cǎrtǎrescu’s narrator find their place: a missing twin; silent strangers which visit him at night; dreams that catapult him out of bed; a wife who changes into someone—or perhaps something—else; the solenoid residing under the foundations of his house. Alongside these anomalies, the narrator traces a line of connections from Ethel Voynich, author of The Gadfly—a novel he connected with as a child—to mathematician George Boole, to Charles Howard Hinton and his four-dimensional tesseract. He recounts the life of Nicolae Minovici, who brought himself to the brink of death in order to see transcendent visions, and the lineage of Nicolae Vaschide, an oneiromancer who could enter other people’s dreams.

Both the things which happen to the narrator as much as the things he obsesses over depict a quest for a hidden reality, for an escape from the prison of our lives and of our three-dimensional experience of the universe. It is so exhaustively done, the narrator’s impressions so meticulously recounted, his ideas so powerfully and comprehensively rendered, that you cannot help but feel you’ve been brought to the very limit of human knowledge, the exciting and exquisite frontier of human understanding.

Reading Solenoid was, for me, akin to seeing the contents of my mind stretched out upon paper. Page after page I was stunned by the extrapolation of theories and obsessions so like the ones that have consumed my thinking since I was an adolescent. Cǎrtǎrescu’s curious mixture of literature and mathematics, physics and metaphysics, oneirology and biology, was for me anything but curious: I saw myself reflected in every thought, but more importantly, I saw reflected a mind so similar to my own that it made me weep. Is this the experience of everyone who reads the text? Do we all harbour within us a secret philosophy, wherein the various disciplines of human thought mix and merge to fantastic result?

In Cǎrtǎrescu I feel I have found a like-mind, but undoubtedly everyone’s personal philosophies are different or else every book would be Solenoid and all humanity would be in agreement. This difference is a blessing but it is also underlaid by sameness: though the content of our philosophies differ, we are each of us caught up in the drive for meaning, for purpose. We’re searching for something, and yet, unbeknownst to us, we’ve also invented the thing we’re searching for: the meaning we find will never be anything other than our own construction.

Solenoid is an impressive feat. It is perhaps the best book I’ve ever read, in part because of how close it appears to bring you to an absolute answer (or something akin to it). I say “appears” because no matter how elaborate, how genius, how revelatory Cǎrtǎrescu’s writing is here, it is, like all other literature, mere distraction from the truth. This is something the narrator of Solenoid himself speaks of again and again throughout the text:

No novel ever gave us a path; all of them, absolutely all of them sink back into the useless void of literature. The world is full of the millions of novels that elide the only sense that writing ever had: to understand yourself to the very end, up to the only chamber in the mind's labyrinth you are not permitted to enter.5

For Cǎrtǎrescu’s narrator, the only meaningful purpose writing can have is to throw open the doors of our prison—to show us the path to freedom, beyond the limitations of our temporally- and physiologically-bound bodies and our three-dimensional experience of the world. But literature, he says, can only ever distract us from this search for escape:

I have wandered through thousands of rooms of the museum of literature, charmed at first by the art with which a door was painted on every wall, in trompe l’oeil, meticulously matching each splinter of wood with a pointed shadow, each coating of paint with a feeling of fragility and transparence that made you admire the artists of illusion more than you've ever admired anything, but in the end, after hundreds of kilometers of corridors of false doors, with the ever stronger smell of oil paints and thinners in the stale air, the route ceases to be a contemplative stroll and becomes first a state of disquiet, then a breathless panic. Each door fools you and disappoints you, and the more completely you are fooled, the more it hurts. They are wonderfully painted, but they do not open. Literature is a hermetically sealed museum, a museum of illusionary doors, of artists worrying over the nuance of beige and the most expressive imitation of a knocker, hinge, or doorknob, the velvety black of the keyhole. All it takes is for you to close your eyes and run your fingers over the continuous, unending wall to understand that nowhere in the house of literature are there any openings or fissures.6

“Novels hold you here,” he writes later, “they keep you warm and cozy, they put glittering ribbons on the circus horse.”7 But only a “real book” can help you escape. The narrator’s obsession with escape is an obsession with being released from the human condition—from the torment and suffering of the human ordeal, wherein our thinking minds are stuffed into disease-prone tissue, into a universe of indifferent violence, into an existence that sooner or later will be snuffed out by the hand of time. He wonders if perhaps gaining access to the four-dimensional universe would grant us freedom, but even then, he concludes, it is likely that any emergence from our world would only be into an even larger prison cell:

. . . reaching the fourth dimension was only an insignificant beginning, the first turn of an asymptotic spiral around the central point, the first move in an infinite ascension up a stairway where each step is two times higher than the previous. Because . . . we could conceive of a world in five dimensions, generated by a hypervolume in movement. The world of four dimensions would be, for this even higher new world, a four-dimensional membrane surrounding a sphere of five dimensions. And this new world would, in turn, be the screen onto which shadows of the six-dimensional world were cast, and each world would be grander, more intense, and truer than the one before, not proportionally so, but madly, asymptotically—something neither the mind nor the gaze could comprehend. . . . When the poor human, waiting in the antechamber of the infinite, dies, the last sound he hears is the simultaneous slam of the infinite number of doors that separate him from the truth, each twice as grand as the one before.8

While achieving escape is both crucial and seemingly possible for Solenoid’s narrator, in our world different rules apply. In the place you and I find ourselves, an answer, an escape, will never be found—not because we aren’t trying hard enough, but because there isn’t one to begin with (at least, not within the limits of human understanding).

Do I think that Solenoid therefore presents us with yet another illusion, yet another painted door that will not open? No, or not exactly. It is a novel so consumed with unravelling the perceived mystery at the heart of existence that, in its attempts to do so, it changes the way one views and experiences the world. I’m not exaggerating when I say that many readers will walk away from this novel changed. What Solenoid communicates to its readers is not the importance of finding an answer, but the importance of trying anyway, despite knowing we will never find it. The inability to achieve telos is beside the point, the novel seems to say: it is the search itself that is meaningful. Without the search, we are lost. Without the search, all meaning dissolves. We must remember that meaning exists only where we create it, that it can only be seen where and if we decide to see it.

The human tendency to construct meaning where there is none is, therefore, not a folly after all—it is a strength. It is what allows us to endure, day after day, century after century, through war and catastrophe, through loss and despair, and in spite of all this to push out ever further into the cosmic unknown, to learn and to understand, and to extend brilliant order into the devouring chaos of meaninglessness that pushes forever at our door.

No one in this world, where everything conspires in the construction of perfect illusions and a corresponding despair, no one can hope if it wasn’t given to him to hope, and they cannot search if they do not have the instinct for seeking engraved in the flesh of their mind. We search like idiots, we look in places where there is nothing to find, like spiders that weave webs in the corner of a bathroom where flies don’t come, where not even mosquitos can reach. We shrivel in our webs by the thousands, but what doesn’t die is our need for truth. We are like people drawn inside of a square on a piece of paper. We cannot get out of the black lines, we exhaust ourselves by examining, dozens and hundreds of times, every part of the square, hoping to find a fissure. Until one of us suddenly understands, because he was predestined to understand, that within the plane of the paper escape is impossible. That the exit, simple and open wide, is perpendicular to the paper, in a third dimension that up until that moment was inconceivable. Such that, to the amazement of those still inside the four ink lines, the chosen one breaks out of his chrysalis, spreads his enormous wings, and rises gently, leaving his shadow below in his former world.9

Thomas Pynchon, Gravity’s Rainbow (Penguin, 2006), 268.

Mircea Cǎrtǎrescu. Solenoid (Deep Vellum, 2022), 311.

Cǎrtǎrescu, 507.

Cǎrtǎrescu, 194-95.

Cǎrtǎrescu, 209.

Cǎrtǎrescu, 41.

Cǎrtǎrescu, 210.

Cǎrtǎrescu, 361.

Cǎrtǎrescu, 79.

Wonderful piece, Shaye! Always so excited to read your words. If you haven’t read it before, I’d highly recommend All the Names by Jose Saramago! Besides being one of my all-time favorites, I think it fits nicely with this essay re: labyrinths, creating/finding meaning, etc.

Thank God your prodigal voice has returned. And with all the force of survival, Sysyphian effort, and stunning impact. This is a beautiful statement. And it will cause a glorious mental indigestion for hours to lifetimes to come. Thank you for bringing it forth. Thank you for laying it open. Thank you for filleting these concepts so skillfully we are left with just the finest cuts, and we are momentarily satiated. But even as we swallow this delicious piece, we hunger for more. So good to have you back up!