9. THE PARADOX OF KNOWING

On doubt, complexity, the limits of knowledge, and the folly of certainty

We are all of us blind—

Think, for a moment, about the vastness of the universe: not simply the incomprehensible swathes of space that exist beyond our little planet’s horizon—space that is mostly empty and yet nonetheless contains trillions (upon trillions) of stars, themselves contained within trillions (upon trillions) of galaxies, grouped into clusters which are moment by moment racing apart from each other as the universe hastily expands—but also the vastness of the small, the incredible cosmos of the infinitesimal, where in each cubic-centimeter we find trillions (upon trillions) of atoms, each its own universe with its own strange workings, whose particles defy our macro laws and the schema of our understanding. It is a space bristling with diversity and complexity; multiple millennia of science (in all its forms) has yet to figure it out. Though we have learnt quite a lot since our ancestors began walking on two feet, our knowledge is only a drop of water in an inconceivably large sea. The greatest achievements in science—the discovery of DNA, the theory of relativity—contribute mere molecules to that droplet. We know so much. We know so little.

In amongst this great complexity it is hard to fathom that we might know anything at all. To know a thing you must first isolate it. To know a cup, you must collect it from the table, turn it about in the light, in mid-air, examining its angles, its colours and textures, its smell and taste. Still, you would not be finished. To know the cup completely, you would need to know its material, its composition: you would need to chop it up and grind it into dust and study its individual molecules. You would need to learn not only the elements of which it is made but also how those elements themselves work, and so the dust must be further divided into atoms, then into particles. And then, to understand the elements which comprise the dust which comprises the cup, you would need to understand the mechanics of quanta, the fantastic workings of the quantum realm, which no one has yet been able to fathom.

And even if here you succeeded, where no one has, you would still be far from knowing the cup, because the cup does not and cannot exist in a vacuum—like everything, it has qualities only because it exists in relation to other things. And so you would next need to set about the exhausting (and inexhaustible) task of understanding the cup in its relations: how it’s qualities change in different contexts, in different cities and countries, in different lights and different temperatures, under different forces and at different times; how its appearance differs when you yourself have changed, when you are in different moods or stages of life; how it is experienced and understood differently by others, and how for these others as well the cup is ever-changing, manifold in appearance and meaning, dependant on time, season, mood and situational context. You would need to know how the cup was made, when it was made, by whom, and every part of the world its constitutive elements passed through on the journey to becoming. You would need to uncover its significance to every person who saw it, who held it, who sold it, who bought it. And from there, even an attempt to understand something as small as a cup would rapidly expand outwards, as, in striving to understand how the cup has been perceived, you would need to understand the perceivers in equal totality; in seeking to understand how the cup has been made, you would need to understand in entirety the tools and the factories that made it; in hoping to know the cup’s history, you would be required to learn the full nature of the landscapes and cities and countries that created and bore it; and in dreaming to understand those people and places, you would need to uncover all the secrets of the world, all the enigmas of the human mind, and all the mysteries of the universe itself.

In short, to arrive at a total knowledge of one thing, you must possess a total knowledge of all things. To know anything entirely, and with certainty, would require the omniscience that is reserved for fantastic tales and for God—or rather, our idea of such a deity.1

As if this weren’t enough, there is yet another problem: absolute knowledge unfortunately amounts to absolute ignorance. Should you arrive at the summit of knowledge, you would find it absolutely opaque, so full as to be empty. When all things are seen in totality, they crowd the image to such an extent that everything becomes indistinguishable from everything else—the knowing of all becomes the knowing of one thing, an absolute which, by virtue or fault of its infinite density, can no longer be said to exist… At absolute wisdom, one becomes the perfect fool.2

Human understanding is bound by the finitude of our physiology. No matter how hard we try, we will never equal the knowledge of God—and perhaps God itself cannot even possess such knowledge. It all pivots on a single question: Can the infinite exist in reality? My gut tells me it can’t. Reality, as I understand it, abhors absolutes; it deals in incomplete pieces, in fragments, some of which fit together, some of which add up, but never to some unified and total whole, never to some thing we could call everything, never to some thing we could call absolute. But one can never be certain.

Mostly, I don’t know what I know. Or rather, I don’t trust myself to know things. I don’t trust the feeling of knowing, because in my certainty I have committed a grave and unscientific error: I have decided that there is no evidence that could prove me wrong. To be certain a thing is true you have to rule out every other alternative, of which there are an infinite number. The human mind, being finite, cannot even conceive of all possible alternatives, let alone cycle through them and methodically dismantle each and every one. Thus, we can never say for sure there isn’t some evidence that could disprove our theories. In choosing to feel certain (and it is a choice, and it is a feeling) I have skipped over the delicate but dangerous line between science and pseudoscience. I have made a religion of my knowledge and trespassed in the territory of faith.

Nonetheless (and perhaps paradoxically), faith is important in science. In knowing that we can never truly know something, there is always a point in the establishment of a theory where we must take a leap: we must choose to believe that the sun will rise again, even through there is no way to be sure it will. We must choose to believe that the world is real, even though we cannot escape the prison of our bodies in order to verify it isn’t a mental concoction. A little faith is important or else nothing would ever get done. No engineer could build a bridge if he didn’t first believe in the ruler. The important thing is that this faith is propped up by evidence that hasn’t yet been disproved. You put your faith in the measurements of the ruler because we have millennia of evidence to suggest they’ll be correct. You wait for the sun because it rose yesterday and every day before. You believe in the world—well, because you have to. Because it’s the most logical and productive thing to do.

And yet, too much faith is a blight. Too much faith makes the thing we call certainty, and certainty is always an error.

It’s true I abhor certainty—I abhor it in myself and I abhor it in others. It strikes me as some kind of human folly, a sign of our inherent limitations. There is simply no way for us to know anything for sure and yet there we go in our billions, as we have for eons, proclaiming this or that knowledge, proclaiming that we have the answer, that we hold the truth, that we know what others don’t, that we and anyone who agrees with us is right and the rest are wrong, all wrong. What is the short circuit in our minds that stops us from remembering that we actually aren’t certain, that we really don’t know for sure? Why do we resist such remembering? Why, when the voice inside us whispers its quiet doubt, do we suffocate it beneath blind and empty arrogance, shout over it with our recursive, shallow claims?

I think many may try to chalk it up to mere ego: a need to feel right, to feel moral, to feel clever, to feel worthy; a desire for the respect of others, and for their continued respect; a fear of being inconsequential or unimportant. This is not incorrect, but I believe (I believe, but am not certain) that something deeper is at work.

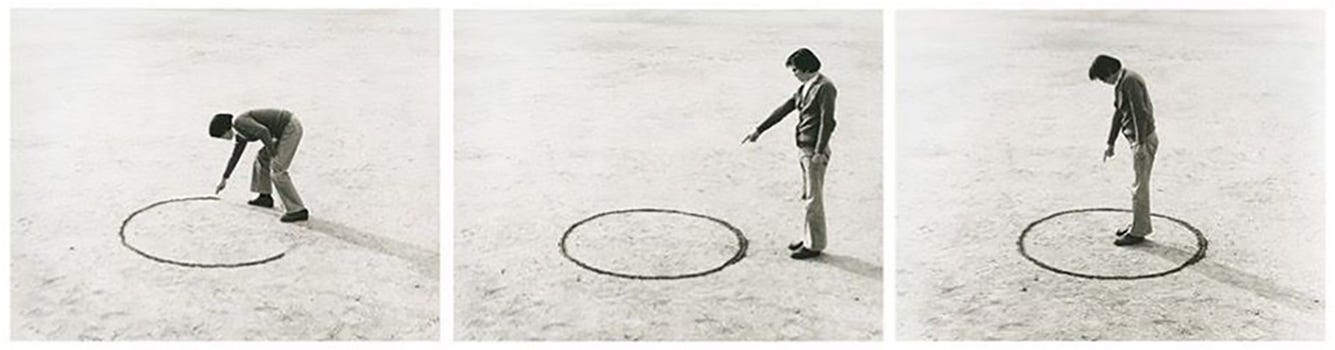

In the abounding complexity of our world, where so much is unknowable, unclear, blurred, vague, where the knowledge of any one thing is necessarily bound up in the knowledge of all else, where definitive statements are outlawed by nature and absolutes can hold no ground—in this large and broken world, whose complexity threatens to wash us away, to shatter our thinking selves, to consume our minds and chew them up and spit them out as pulp, to blow apart all logic, all reason, all purpose, all meaning, to tear us apart at the seams, we cannot survive without shelter. We cannot live without walls to protect us from the annihilating abyss. Thus, to cope, we limit ourselves: we draw borders around our ideas. We think in reduced arenas and refuse to look at what exists outside the perimeter. We put reality into boxes and we ignore, as much as we can, the pieces that don’t fit. We draw digestible patterns over the world and count as extraneous all that doesn’t conform to the design. We are, at heart, pattern-seeking creatures. We cannot abide what does not have order. We cannot bear it.

This need for simplicity, for pattern, is bound to our nature. We didn’t evolve to contemplate the complexity of the universe and so our minds aren’t structured to handle it. We are local creatures and our minds require local borders. Thus, when confronted with the knowledge of all we don’t know, we ignore it. We treat our theories and opinions as certain because to see them otherwise, to remember that we can never know for sure, that complete knowledge is forever out of reach, would be to expose ourselves to devouring beast that is complexity, that is the abyss, that place were no truth can hold, where there is no meaning and no hope.

In these conditions, to say I don’t know is an act of courage. If you admit to yourself that you don’t really know anything, you will daily court annihilation. And I say daily because you will have to do this every day—every day you will have to remind yourself that you don’t know, that you can’t be sure, because our minds are resistant to discomfit, to disorder, to incompleteness; they will revert to factory settings while you sleep or the second you get distracted—when the kettle boils, when the neighbour’s dog starts barking, when a text pings on your phone, when you cook, when you eat, when you laugh, when you dress, when you look at the time and realise you’re late, when you watch a film, when you have drinks with friends, when you shower, when you read, when you remember the dishes need to be cleaned and the floors swept, when you begin to speak of other things, sometimes even in the space between one breath and the next, leaving you to start from the beginning again and again and again.

But you do it, and should do it, because if you don’t nothing you believe is worth anything. No opinion you hold can be trusted. Only the person who has admitted that they can’t be certain, who has stared the complexity of things in the eye, who has seen the impossible task before them and forged ahead anyway, who has investigated all the possibilities they can and who continues to investigate them every day, never settling rigidly in one position, never staking their ground, holding their beliefs but never binding themselves to them, never depositing their identity and self-worth in some limited and flimsy set of words—only this person can confidently say anything, because they have accepted that they could be wrong, because the ideas they hold as true are only those for which they’ve seen evidence, because they are constantly searching for evidence to the contrary, and because the second they find it they will allow their beliefs to change.

It is a hard world we find ourselves in. Nothing about it is consistent or simple. We are beings comforted by pattern and yet we are stranded in a disordered reality. We seek truth in a world where truth cannot be found. In needing something to hold on to, some buoy to cling to while the sea rages, I have latched onto this idea, just another in an infinite series: that there is nothing that can be known. I have, like all the others, climbed my hill, staked my ground, proclaimed I have the answer, placed my identity in the hold of these fragile words. And is this not the greatest irony?

I am certain that nothing can be known for certain. What an awful, inescapable loop. What a terrible, all-consuming paradox. Even that I cannot know. Even this. And this. And this—

—all we do is see, and all we see is nothing.

Speaking of God here, I speak not of the Christian god (though the Christian god could be considered the equivalent of this one—some will disagree with me here) but of God the placeholder, God the limit, God as the symbol for the infinite, the absolute, and the unknowable.

But truly, this is a topic for another day…

The universal nature of physical laws makes the intractable infinitude somewhat smaller. To understand the cup one has to know what happens when it falls to the ground, how fast it moves in each second, what happens when it finally encounters the point of impact and so on. But in fact, one doesn’t need to do any of this, because there are patterns like gravity and mechanics and electromagnetism that imply that once one has this knowledge for one cup, one has it for all cups, but also for all people, and lo and behold, for all planets.

At some point, this miraculous edifice of universal laws develops cracks and new theories have to be forged in an ever growing tower of babel, but yet again, they expand the scope of predictability for a huge variety of phenomena in one fell swoop. Thus the claim that “for each object one has to construct the endless web of facts anew” has to be qualified. For if this were truly the case, we would only have a science of the Particular, which would grind understanding to a halt.

If this were not beautiful circus of coincidences enough, in fact there are patterns that sustain even beyond their original context.

For example, the Lagrangian-Hamiltonian formulation was conceived as an alternative to Newton’s formulation of macroscopic physics providing conceptual clarity but as such no extra empirical power, but later it magically turned out to apply to the quantum realm as well, where Newton’s laws completely fail.

Another example is Darwinian natural selection by random mutation, which was proposed as an explanation for the origin of species, but now is used to create “genetic algorithms” that find close to the optimal solution not by explicit human engineering but by exploring the landscape of possibilities subject to a fitness maximisation constraint. Lee Smolin raises the stakes to the cosmological level by proposing an evolutionary process over Universes! (highly speculative, obviously).

Sometimes, once you discover a profound way of modelling the world in one realm, it turns out to encompass far more than your initial ambitions. Some keys open more locks than one.